Why do 70% of Gen Z watch TV with subtitles? Discover the truth about the "Downmix Disaster," Christopher Nolan's mixing style, and why modern movies are so hard to hear.

Brajesh Mishra

Brajesh Mishra

Imagine It’s 9:00 PM and you are watching House of the Dragon. The dragon roars, shaking your floorboards. The score swells to a Hans Zimmer-level peak. It is cinema in its purest, loudest form.

Then, the scene cuts to two characters standing in a dimly lit stone corridor. The Hand of the King leans in to whisper a secret that changes the entire plot. You lean forward. You squint. You hold your breath.

“mumble mumble mumble treason.”

You didn’t catch it. You grab the remote, rewind ten seconds, and turn the volume up, you listen again and still nothing. Frustrated, you do the only thing left to do. You toggle the setting that has become the defining scar of our media generation.

Subtitles: [ON]

You aren't going deaf. In fact, if you are reading this, you are likely a Millennial or Gen Z with statistically "perfect" hearing. Yet, you are part of a massive demographic inversion.

According to data from Preply and YPulse, 70% of Generation Z uses subtitles "most of the time," compared to just 35% of Baby Boomers and for the first time in history, the generation with the healthiest ears is the most reliant on assistive text. We have inverted the hierarchy of the senses. We are witnessing a "Text-First Transition." We no longer watch TV; we read it.

But why? Is it our attention spans? Our speakers? Or is Hollywood conspiring against us? To find the answer, we have to look beyond the screen: into the physics of our living rooms, the biology of our brains, and the arrogance of modern art.

If you ask the average viewer why they use subtitles, they will immediately point a finger at the screen saying "The actors are mumbling," and "The music is too loud."

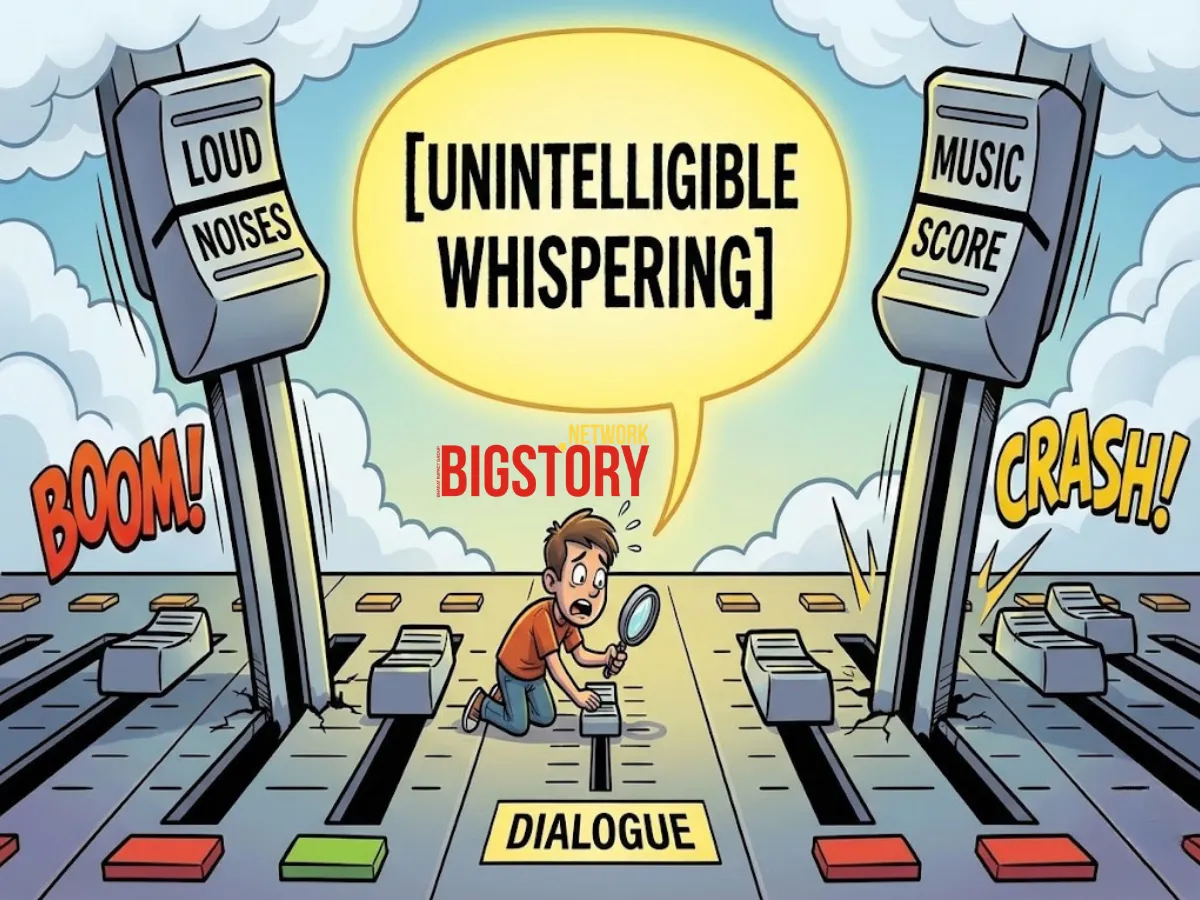

However they aren't wrong. They are the collateral damage of a technical war happening inside their televisions, The War of "Loud vs. Quiet" and to understand the problem, you have to understand where movies are made. Films are mixed in "dubbing stages" in acoustically treated bunkers with expensive sound systems and absolute silence. In this pristine environment, a sound engineer can place a whisper at 40 decibels (dB) and an explosion at 110dB. This 70dB gap is called High Dynamic Range.

In a theater, it’s thrilling. The silence draws you in; the explosion blows you back, but when you are in an apartment, your air conditioner is humming, your dishwasher is running, traffic is outside and when you play that theatrical mix at home, the "whisper" falls below the noise floor of your room making it physically inaudible.

So, you turn the volume up to hear the dialogue, but because the "Dynamic Range" is locked, raising the whisper also raises the explosion. Suddenly, a car door slamming sounds like a gunshot and you scramble for the remote to avoid waking the baby or alerting the neighbors. You are trapped in the "Remote Control Ride" frantically turning the volume up for talking and down for action, naming it The "Downmix" Disaster but on a broader look, the volume is only half the battle and The real killer is math.

"Most blockbuster movies are mixed in advanced audio formats like 7.1 Surround Sound or Dolby Atmos. In these setups, the dialogue is isolated on its own speaker, the Center Channel, separate from the music (handled by the Left/Right speakers) and the sound effects (managed by the Surround speakers).

However, when played on a device with only two speakers—such as a laptop, iPad, or standard TV, the device's audio processor must combine those seven audio channels into a two-channel stereo signal known as "Downmixing."

During a downmix, the dialogue (Center Channel) is mathematically "folded" into the Left and Right speakers. But to prevent it from blowing out the speakers, standard engineering protocols reduce the dialogue by -3dB.

Think about that. The most important part of the movie, the words, is being actively turned down while being shoved into the same speaker as the explosions. It’s like trying to have a polite conversation in the middle of a mosh pit.

The Arrogance of Art Is this a mistake? No. It is a choice.

Director Christopher Nolan (Tenet, Oppenheimer) has become the figurehead of the "Inaudible Cinema" movement. Nolan shoots with massive IMAX cameras that sound like lawnmowers. Most directors would use ADR (Automated Dialogue Replacement) to re-record clean dialogue in a studio later. Nolan refuses. He prefers the "raw emotional performance" on set, even if it’s muffled by camera noise or gas masks.

Sound editor Donald Sylvester puts it bluntly: "I think Christopher Nolan wears it as a badge of honor... I don't think he cares. I think he wants people to give him bad publicity because then he can explain his methods."

Nolan’s philosophy is "Impressionistic Sound." He believes you shouldn't intellectually process every word; you should "feel" the scene. For the Gen Z viewer, who values information clarity ("What exactly did he say?"), this artistic ambiguity feels less like art and more like a broken product.

While Nolan breaks the mixing board, the actors are breaking the microphone. We have entered the era of "Mumblecore" acting.

In the mid-20th century, Hollywood utilized the "Transatlantic Accent": a crisp, artificial style of enunciation designed to be heard in the back row of a cavernous theater and today, under the influence of "Method Acting" and hyper-realism, the goal is no longer projection; it is intimacy.

Take Tom Hardy, an actor famous for his unintelligible grunts in The Dark Knight Rises or Taboo. Or look at the hit show "The Bear."

The sound design of The Bear is weaponized chaos. It uses a technique called "Overlapping Dialogue": chefs shouting "Corner!" and "Behind!" over the sizzle of meat, the clatter of pans, and the hum of ticket machines.

This is "Audio Vérité." It is designed to induce anxiety, to make you feel the stress of the kitchen. But when that complex "auditory soup" is downmixed to a stereo TV, it turns into muddy sludge. The brain cannot separate the voices from the noise because, unlike in real life, they are all coming from the exact same spatial location (your TV speakers).

Succession does the same thing with "throwaway lines." Characters mutter insults under their breath or while walking away from the camera. For a fan, missing a "Cousin Greg" stammer is missing the best joke of the episode. Subtitles are the only way to catch the nuance that the microphone barely picked up.

The actors aren't speaking to you, the audience. They are speaking to each other. And without subtitles, you are just eavesdropping through a glass wall.

While audio engineers argue about dynamic range, they are ignoring the single biggest source of noise pollution in the modern living room: The Snack.

It drives a phenomenon known as the "Bone Conduction Effect." It sounds funny, but it is pure physics. When you eat crunchy food (chips, popcorn, pretzels), the sound of the crunch doesn't just travel through the air to your ears. It vibrates through your jawbone directly into your inner ear, creating a temporary "masking threshold." Every time you crunch, you essentially deafen yourself to the TV for a split second.

As one Reddit user famously posted: "Subtitles are used more by people eating chips than by the deaf."

This leads to the "Pavlovian Subtitle Response." You sit down with a snack. You know you won't be able to hear. You turn the subtitles on. Eventually, the snack is gone, but the habit remains. The subtitles stay on forever.

And it’s not just snacking. We live in the "Architecture of Politeness." With high rent forcing us into apartments with roommates and paper-thin walls, we can no longer blast the volume. We generally tend to shy away rather than annoying somebody. Subtitles allow us to "acoustically contain" our entertainment as well as letting us follow the plot without projecting our presence into the next room.

If the audio is the "Villain," then your smartphone is the accomplice. We are the "Second Screen" Generation.

The Attention Anchor Watch a teenager watch a movie. Their eyes are on the TV, but their phone is in their hand. They are scrolling TikTok, replying to texts, or checking IMDb.

Cognitive scientists call this "Continuous Partial Attention." Listening requires sustained, linear focus. If you look away for three seconds to read a text, the audio stream is broken. You miss the context.

Subtitles act as a Visual Anchor. They allow you to "multitask reality." You can look down at your phone, look up, scan the subtitle block in 0.5 seconds (because reading is faster than listening), and instantly "download" the plot points you missed. You don't have to rewind. You don't have to ask, "What happened?" The text waits for you.

The "TikTok" Brain We have also been conditioned by social media interfaces.

We have spent the last decade consuming content where text and video are fused. To a Gen Z viewer, a screen without text looks "naked." The brain now craves "Dual Coding": the reinforcement of hearing the word and seeing the word simultaneously. It feels more "complete."

There is a final, darker psychological layer: Control.

In an uncertain world, we crave certainty. Subtitles guarantee 100% information capture.

Yes, subtitles often ruin the punchline of a joke by displaying it seconds before the actor says it. But we don't care. We prefer the certainty of reading the joke to the risk of not hearing it. This is the "Spoiler Paradox."

This is why "Ending Explained" videos are now so popular on YouTube. We are terrified of ambiguity. We don't want to "interpret" the film; we want to "solve" it. Subtitles turn a movie into a dataset—clear, readable, and impossible to misunderstand.

We aren't going deaf, We are adapting. The rise of subtitles is a rational response to an irrational environment. We are watching movies mixed for theaters that don't exist, on speakers that are too small to do them justice, in rooms that are too loud, while eating food that is too crunchy, with attention spans that are too fractured.

Turning on the subtitles is our white flag. It is our way of saying to Christopher Nolan, to the sound engineers, and to our own chaotic lives:

"I cannot give this art my full attention. I cannot fight the physics of my living room. So please, just give me the summary."

The movies haven't gotten quieter. The world has just gotten too loud.

But surrender isn't your only option. If you aren't ready to accept a text-only future, if you want to turn the subtitles off and actually listen again, you have to fight the physics and here is your battle plan.

1. The "Night Mode" Hack Every modern TV (LG, Samsung, Sony) has a setting hidden deep in the audio menu. It is usually called "Night Mode," "Dynamic Range Compression," or "Reduce Loud Sounds."

2. The Center Channel Boost If you have a soundbar, look for a button on the remote labeled "Voice," "Dialogue," or "Center." This uses EQ to artificially boost the frequencies of the human voice (1kHz–4kHz). It cuts through the "mud" of the bass.

3. The AI Renaissance The tech giants know this is a problem.

Why do so many young people use subtitles?

According to data, 70% of Gen Z use subtitles despite having good hearing. This is due to the "Text-First Transition," where subtitles serve as a "cognitive tether" allowing viewers to multitask on their phones (second screening) while instantly "downloading" plot points they missed visually.

Why is movie dialogue so hard to hear on modern TVs?

The primary cause is "High Dynamic Range" audio mixing. Movies are mixed for quiet theaters with a huge gap (up to 70dB) between whispers and explosions. When played on home TVs, the "whisper" falls below the room's noise floor, and raising the volume makes explosions dangerously loud.

What is the "Downmix Disaster"?

Most blockbusters are mixed in 5.1 or 7.1 surround sound where dialogue has its own speaker (Center Channel). When watched on a laptop or TV with only two speakers, the audio processor "downmixes" these channels together, often lowering the dialogue volume to prevent speaker blowout, making speech muddy.

Why does Christopher Nolan's movie audio sound muffled?

Director Christopher Nolan prefers "Impressionistic Sound." He refuses to use ADR (Automated Dialogue Replacement) to re-record clean lines in a studio, preferring the raw, sometimes muffled, on-set performance even if it is obscured by IMAX camera noise or masks.

What is the "Bone Conduction Effect" in watching TV?

The "Bone Conduction Effect" occurs when eating crunchy snacks like chips or popcorn. The chewing vibration travels through the jawbone directly to the inner ear, creating a temporary "masking threshold" that deafens the viewer to the TV audio, prompting the use of subtitles.

Sign up for the Daily newsletter to get your biggest stories, handpicked for you each day.

Trending Now! in last 24hrs

Trending Now! in last 24hrs