An investigation into how high banker fees, valuation lies, and founder exits rig the market against the common investor.

Minaketan Mishra

Minaketan Mishra

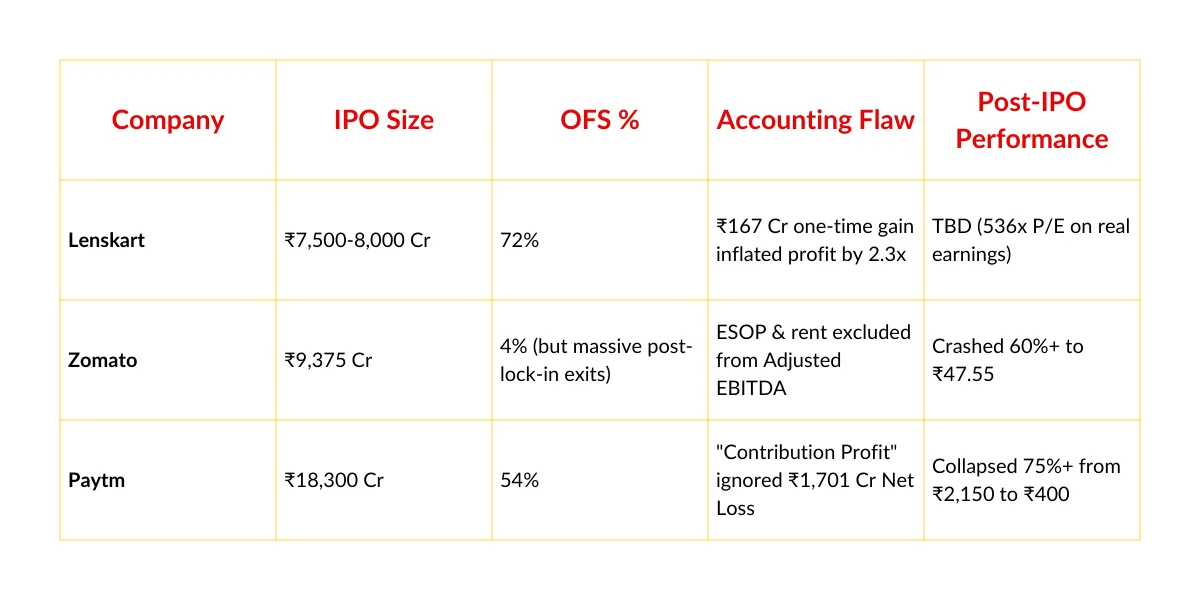

Remember Jaspal Bhatti's classic sketch—PP Waterballs IPO? A pani puri stall registers as a company, floats an IPO, and vanishes with public money. We laughed because it was absurd. But here's the uncomfortable truth: India's "New-Age Tech" IPOs—Paytm, Zomato, Lenskart—have perfected that same scam, except they do it legally, in broad daylight, with SEBI's stamp of approval and Goldman Sachs counting the fees.

This is not a story about market volatility or bad timing. This is a forensic exposé of a systemic wealth transfer mechanism disguised as capital formation. The losses suffered by retail investors in these IPOs are not accidents—they are the predictable, structural outcome of a process engineered to serve one purpose: making insiders rich and leaving the public to clean up the mess.

The evidence is damning. Through a granular analysis of regulatory filings, financial disclosures, and expert commentary, three patterns emerge with mathematical precision:

Let's decode the golmaal, step by step.

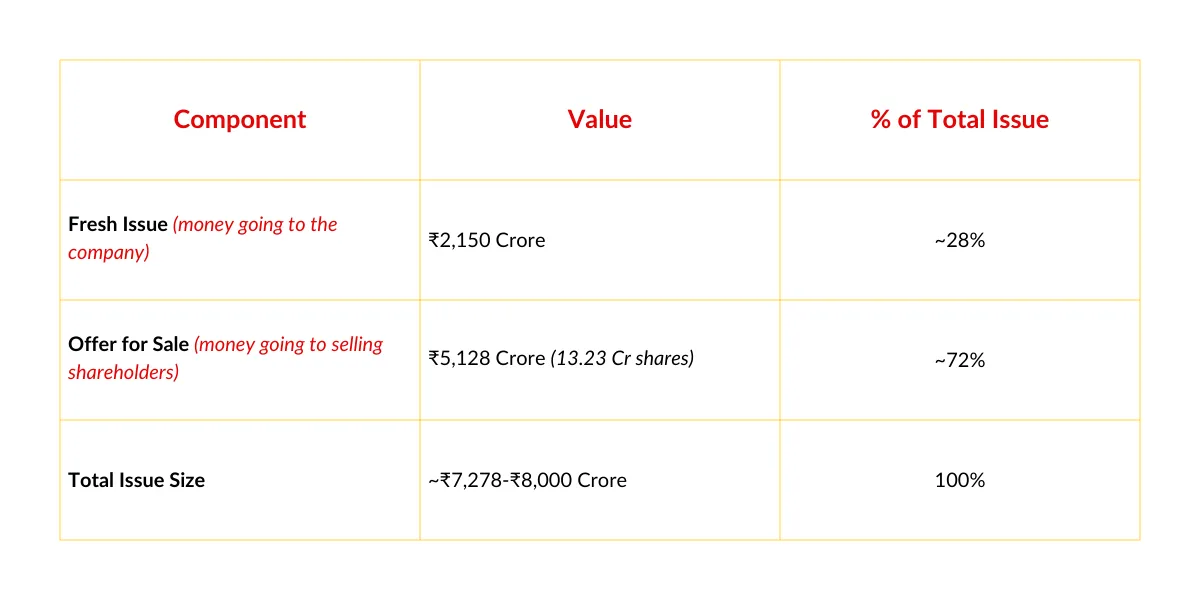

In July 2024, Lenskart Solutions filed its Draft Red Herring Prospectus (DRHP) aiming for a valuation of ₹60,000-₹70,000 crore. The headlines celebrated another "unicorn" going public. But the fine print told a different story—one of exploitation and the "make me rich and forget me" attitude that now defines India's IPO market.

The numbers don't lie:

Read that again. 72% of the capital raised from the public does not go to Lenskart for opening new stores, building technology, or expanding operations. It flows directly into the bank accounts of founder Peyush Bansal and institutional investors like SoftBank's SVF II Lightbulb.

This is not an Initial Public Offering. This is a Secondary Public Sale—an exit door for insiders who want to cash out at peak valuation, leaving retail investors holding the bag when reality sets in.

When nearly three-quarters of an IPO is effectively a liquidation event, the narrative of "funding future growth" becomes a fiction. The question retail investors should ask is simple: If the company needs capital to justify its ₹70,000 crore valuation, why is the Fresh Issue so small? The answer is uncomfortable—either the company doesn't need the money (making this purely an exit vehicle), or the insiders believe the current valuation represents a peak they won't see again.

This is the financial equivalent of road contractors: "Give me the money and forget me." Except unlike contractors, these companies do it with merchant bankers applauding and retail investors lined up to hand over their savings.

Zomato's July 2021 IPO appeared more balanced on paper—₹9,000 crore Fresh Issue vs. only ₹375 crore OFS (about 4%). The low OFS created artificial scarcity, driving the stock from its issue price of ₹76 to a peak of ₹169 within months. Retail investors celebrated. The "India Growth Story" was real.

Then came July 2022—the one-year lock-in expiry.

The floodgates opened. The marquee investors who had entered at pre-IPO valuations (often ₹10-₹30 per share equivalent) finally had regulatory permission to exit. And exit they did:

The result? Zomato shares plunged to a record low of ₹47.55 in July 2022—a 60%+ collapse from the peak, wiping out over ₹50,000 crore in market capitalization.

Here's the structural scam: These VCs entered at ₹20-₹30 equivalent. They could sell at ₹50 and still book 2-3x returns. The retail investor who bought at ₹76 (IPO price) or ₹140 (peak hype) was left with a 40-70% loss. The risk was systematically transferred from those who knew the company's limitations to those who believed the growth story.

Aswath Damodaran, the legendary valuation expert from NYU Stern, cut through the noise:

"It looks like these companies are less interested in raising capital and more in getting the right pricing and liquidity, which allows existing owners to cash out."

Source: Inc42, Musings on Markets

The IPO wasn't designed to fund Zomato's expansion. It was designed to provide exit liquidity for "smart money" at the expense of public market sustainability. When the lock-in expired, the structural ceiling on the stock price became obvious—there were simply too many insiders waiting to sell.

If Lenskart is the blueprint and Zomato the cautionary tale, Paytm is the catastrophe.

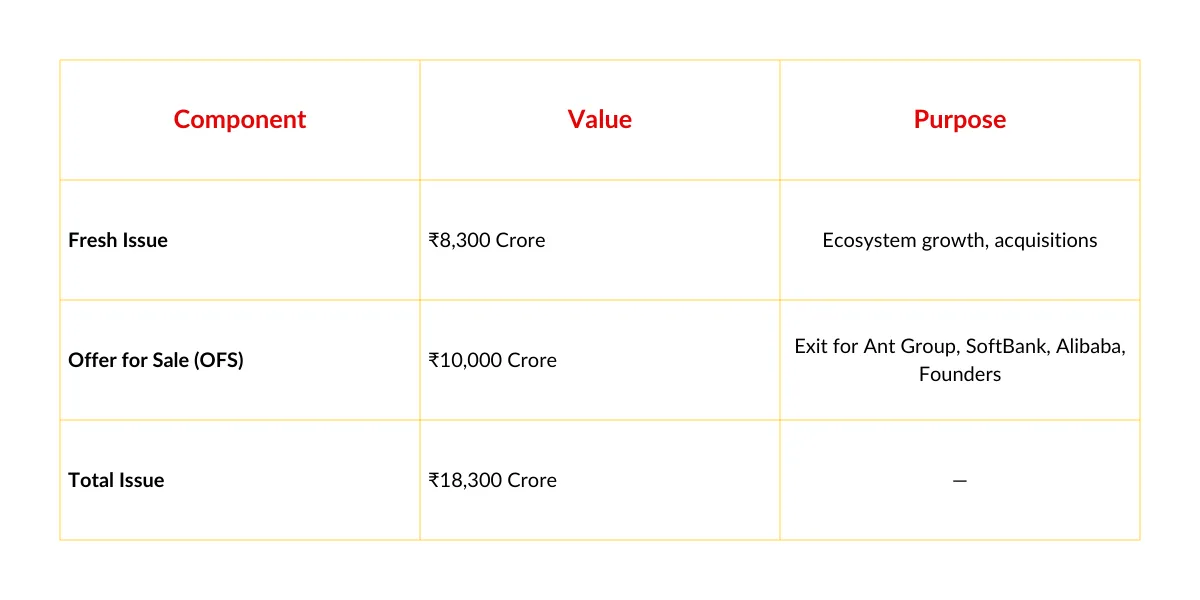

Paytm's November 2021 IPO was the largest in Indian history at ₹18,300 crore. The excitement was palpable—India's fintech giant, backed by Alibaba, SoftBank, and Ant Group, was finally going public. What could go wrong?

Everything.

More than 54% of the capital raised was wealth transfer—money moving directly from public investors to private shareholders. Ant Group, SoftBank, and other early investors secured their exits at ₹2,150 per share. Meanwhile, retail investors who believed in the "India Digital Payments Revolution" saw the stock list at a 9% discount (₹1,950), trigger the lower circuit on day one (₹1,564), and eventually collapse to below ₹500—a 75%+ wipeout.

The selling shareholders walked away with ₹10,000 crore. Retail investors lost lakhs of crores. This wasn't a market correction. This was a structural design flaw masquerading as an IPO.

Market analysts flagged the high OFS as a red flag before the listing, noting that the ₹18,300 crore valuation was being justified primarily to facilitate these massive exits, not based on cash flow or profitability. But by then, the merchant bankers had already done their job—selling the dream, pricing for perfection, and collecting their fees.

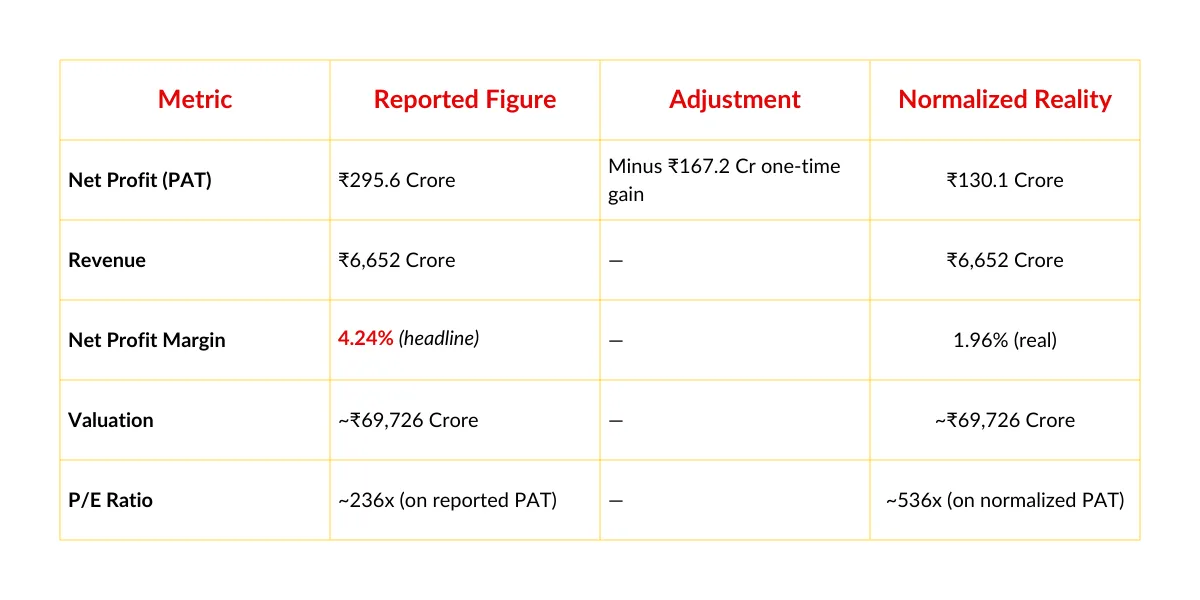

In the lead-up to its IPO, Lenskart unveiled a financial turnaround that seemed miraculous. For FY25, the company reported a Profit After Tax (PAT) of ₹295.6 crore—a stunning reversal from a ₹68 crore loss in FY23. Headlines celebrated: "Lenskart Turns Profitable!" The narrative was set: a mature, profitable unicorn ready for public markets.

But forensic accounting tells a different story. Golmaal hai bhai, sab golmaal hai.

Buried in the disclosures was a single line: Lenskart's reported profit included a ₹167.2 crore one-time, non-cash gain from a "deferred consideration adjustment" related to the acquisition of Japanese eyewear brand Owndays in June 2022. This wasn't cash from selling eyeglasses. This was an accounting entry—financial engineering.

The Profit Quality Reconciliation:

Let that sink in. A normalized profit of ₹130 crore is being asked to justify a ₹70,000 crore valuation—a 536x Price-to-Earnings ratio. To put this in perspective, even high-growth tech giants in mature markets rarely trade above 50-80x P/E. Lenskart is asking retail investors to bet that it will grow profits by 7-10x within a few years, flawlessly, with no competition or execution risk.

This is not valuation. This is speculation dressed up as analysis. And the one-time gain that inflated the headline profit by 2.3x? That's the golmaal—the accounting sleight-of-hand that makes a thin-margin, capital-intensive retail business look like a tech unicorn.

Analysts noted that excluding this adjustment makes the valuation "difficult to justify," implying the IPO pricing has baked in "years of perfect execution that has not yet occurred." Translation: You're being sold tomorrow's dream at today's peak price, with yesterday's accounting trick hiding the risk.

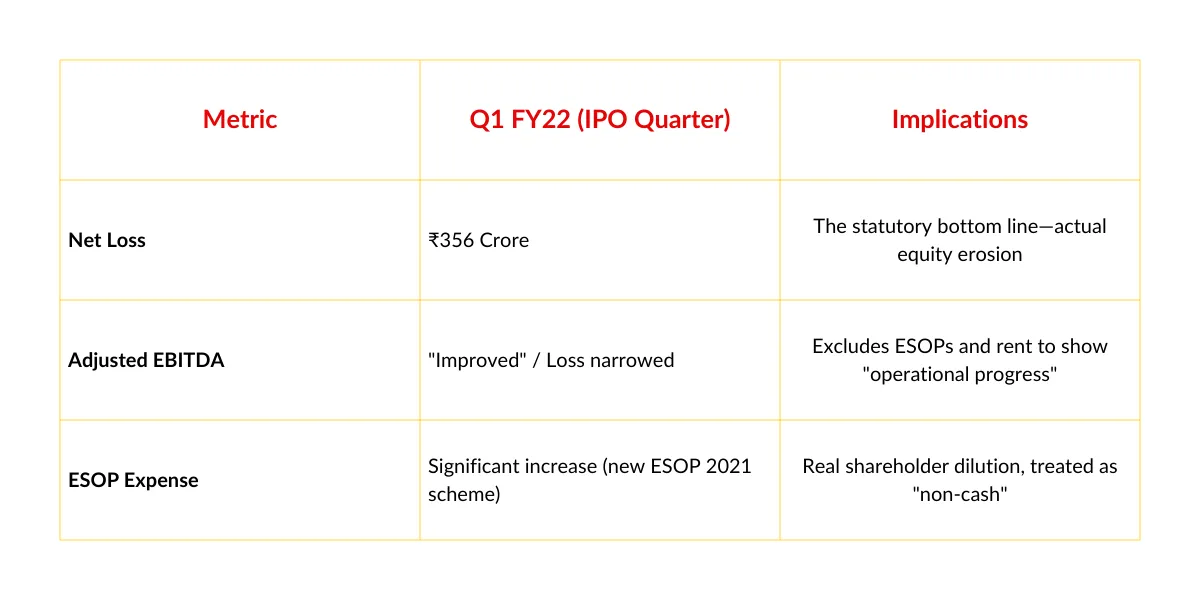

If Lenskart used a one-time gain, Zomato pioneered the art of "creative" metric exclusion—specifically, the infamous "Adjusted EBITDA."

EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization) is supposed to approximate operating cash flow. But Zomato's "Adjusted" version excluded two massive, real costs:

The divergence was staggering:

Zomato touted "Adjusted EBITDA improvements" while bleeding ₹356 crore in actual losses in the quarter it went public. The company was burning cash, issuing massive stock grants to employees (diluting existing shareholders), and paying substantial rent—but all of this was swept under the rug of "adjustments."

Valuation guru Aswath Damodaran explicitly called out this practice:

"And no, you cannot add back stock-based compensation and come up with an adjusted EBITDA to claim otherwise..."

Source: NYU Stern, Zomato Update Analysis

Eventually, even Zomato had to admit the game was up. From Q2 FY23 onwards, the company was forced to include actual rent paid in its Adjusted EBITDA, effectively admitting the previous metric "did not appropriately reflect cash profit/loss."

This is the anatomy of the distraction. By focusing investor attention on a sanitized, "adjusted" metric, Zomato diverted scrutiny from the massive bottom-line hemorrhaging. It justified a ₹9,375 crore IPO valuation that the market eventually corrected—violently.

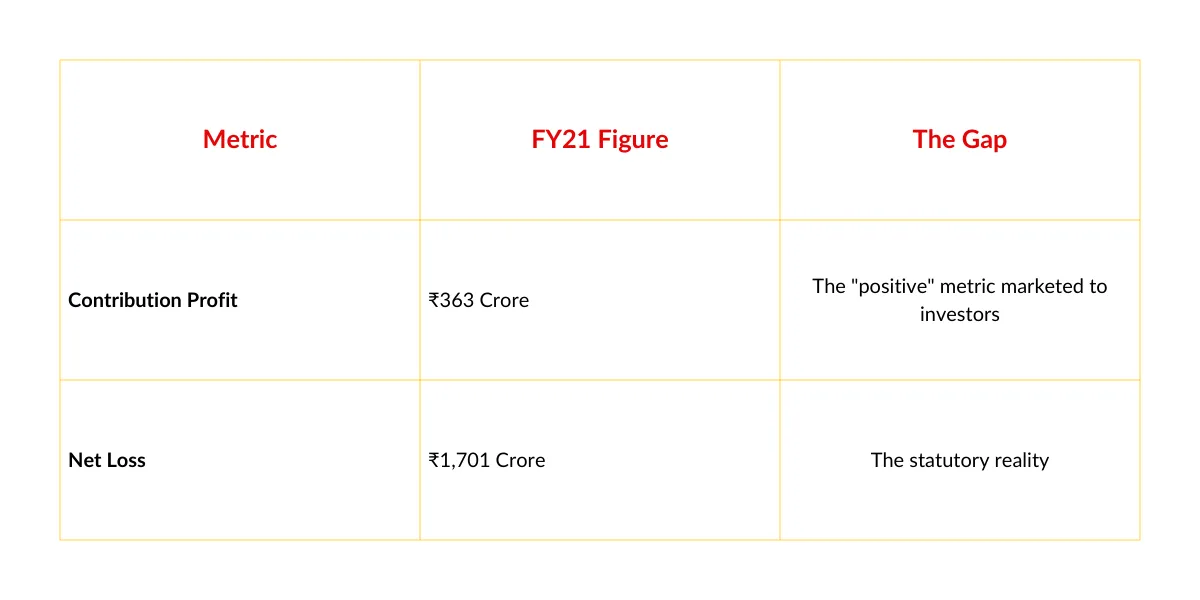

Paytm took metric engineering to its logical extreme with "Contribution Profit"—a term that sounds sophisticated but is functionally meaningless for valuation.

Contribution Profit Definition: Revenue minus Payment Processing Charges and Promotional Expenses.

What it excludes: Employee costs (including massive ESOPs), technology infrastructure, administrative expenses, depreciation, interest, taxes—essentially, every fixed cost required to run the business.

In the lead-up to the IPO (FY21), Paytm touted a Contribution Margin of 30% and a Contribution Profit of ₹363 crore. This was the metric sold to investors during roadshows. It sounded healthy. It suggested positive unit economics.

The reality:

The ₹2,064 crore gap between "Contribution Profit" and Net Loss is the elephant in the room. It represents the colossal fixed costs, ESOP expenses, and infrastructure burn required to run Paytm—costs that don't disappear just because you exclude them from a custom metric.

The "Contribution Profit" narrative suggested: "If we just scale up, we'll be profitable—the unit economics work!" But scaling a loss-making structure doesn't create profitability—it scales the losses. Which is exactly what happened post-IPO.

By focusing retail attention on the 30% Contribution Margin, Paytm diverted scrutiny from the ₹1,701 crore cash burn. This financial engineering allowed them to market the IPO at ₹2,150/share—a valuation that collapsed almost immediately as the market reverted to valuing actual profitability (or the lack thereof).

This wasn't disclosure. This was distraction.

New-age tech companies use Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs) as a core recruitment and retention tool. The pitch is seductive: "Take a lower cash salary now, but when we IPO, you'll be wealthy. You're not just an employee—you're an owner."

For thousands of young engineers, product managers, and delivery partners, this promise justified the 10-hour (often 12-hour) shifts, the weekend work, the constant pivots, and the toxic urgency. They weren't just building a company—they were building their future wealth.

Then the IPO happened. The VCs exited. The stock crashed. And the ESOPs became worthless.

Imagine you're a mid-level software engineer at Zomato in 2021. You've been granted 10,000 ESOPs at an exercise price of ₹40. The company goes public at ₹76. Within months, the stock hits ₹169. On paper, you're a crorepati. You've made promises to your family—a house, your sibling's education, maybe even starting your own venture someday.

Then July 2022 arrives. The one-year lock-in expires. Uber sells its 7.8% stake. Tiger Global exits completely. Alibaba dumps shares. The stock crashes to ₹47.55.

Your ESOPs, which were worth ₹16.9 lakh at the peak, are now worth ₹4.75 lakh—if you can even sell them. If your exercise price is ₹40 and the market price is ₹47, you have ₹70,000 in gains left—barely enough to cover a few months of EMIs on the promises you made.

This is the emotional reality the document describes:

"Reports surfaced of employees feeling exploited, with stories of '10-hour shifts' and a high-pressure work culture being justified by the promise of ESOPs. When the stock crashed from its post-IPO highs of ₹160+ to below ₹40 in 2022, the 'paper wealth' of thousands of employees evaporated."

Source: Reddit discussions, Moneylife

You wouldn't just feel betrayed. You'd enter a state of panic. All the promises you made to yourself and your family—they're gone. You'd stop believing in systems. You'd watch everyone around you become resentful, cynical. You'd realize that nothing is more valuable than money—not even loyalty.

And when morality collapses like that, the entire ecosystem suffers. No company gets good employees to grow. The job market becomes transactional. Innovation dies. The long-term damage spreads far beyond one stock price.

Meanwhile, the founders and VCs who sold their stakes at ₹100-₹150? They're fine. They exited. They got rich. You were the exit liquidity.

If Zomato's story is about betrayed employees, Paytm's story is about betrayed principles.

Typically, "Promoters" (founders and controlling shareholders) are not eligible for ESOPs in India—the logic being that they already own significant equity and shouldn't enrich themselves further at the expense of minority shareholders. But Vijay Shekhar Sharma (VSS), Paytm's founder, found a loophole.

VSS was classified as a "professional managing director" rather than a promoter. This allowed him to be granted 21 million ESOPs—worth approximately ₹1,800 crore at the time of the IPO.

Proxy advisory firms and investors cried foul. This was a founder with majority control receiving ESOPs meant for employees—a clear case of self-enrichment through shareholder dilution. Under regulatory pressure, VSS eventually surrendered the 21 million unvested ESOPs in April 2025.

The financial impact:

Source: Compliance Calendar, YourStory, Moneylife

But here's the bitter irony: By the time VSS surrendered the ESOPs, the stock had already collapsed from ₹2,150 to below ₹500. The ₹1,800 crore valuation was fictional. Retail investors, who bought at ₹2,150, had already lost 75%+ of their capital. VSS gave up options on a sinking ship—a symbolic gesture that cost him nothing but gave regulatory optics.

This is the governance asymmetry: The founder attempted to grant himself ₹1,800 crore in equity while retail investors—who provided the liquidity for the IPO—were left holding losses. The rules were bent to benefit the "big fish," while the common investor paid the price.

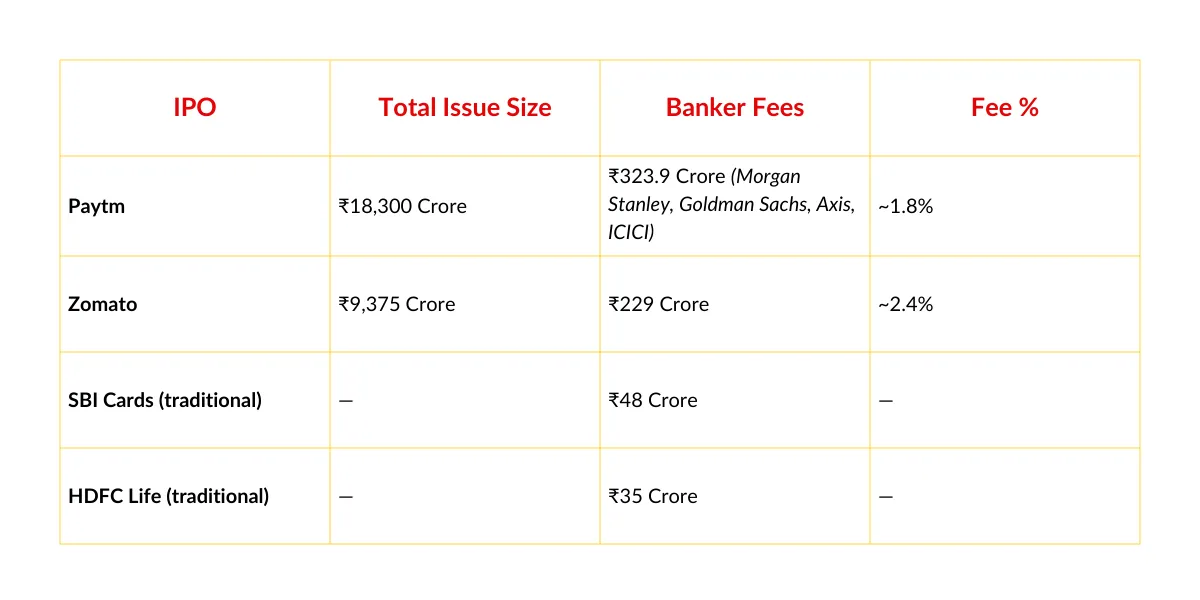

If the structure is rigged (Section 1) and the metrics are fake (Section 2), how do these IPOs get priced so high? The answer lies in the incentive structure of merchant bankers—the supposed "gatekeepers" of the market.

Merchant bankers (investment banks) are compensated based on the size of the IPO. The higher the valuation, the larger the issue size, the bigger their fee. This creates a structural conflict of interest: bankers are incentivized to maximize the price, regardless of whether that valuation is sustainable or fair to retail investors.

The numbers:

Paytm's ₹324 crore fee pool was one of the largest in Indian IPO history—nearly 10x the fees for traditional, profitable company IPOs like SBI Cards or HDFC Life. The correlation is obvious: Higher valuations = Bigger fees.

In 2021, investment banking fees in India hit a record $1.1 billion, driven almost entirely by these massive tech IPOs. The bankers weren't performing independent due diligence or ensuring fair pricing—they were acting as salesmen for the selling shareholders, maximizing the exit price to maximize their own compensation.

SEBI has noted instances of conflict of interest where merchant bankers or their associates held shares in the issuer company, compromising independent analysis. The "gatekeepers" became enablers of overvaluation.

Paytm's IPO price of ₹2,150 per share was described by every independent analyst as "priced for perfection." This wasn't a valuation based on current fundamentals—it was a bet that:

All of these assumptions were statistically improbable. But the price was set there anyway—because the bankers needed a high valuation to facilitate the ₹10,000 crore OFS and maximize their fees, and because the selling shareholders wanted to extract maximum value.

The result:

Vijay Shekhar Sharma later blamed the investment bankers for the poor debut, comparing his listing unfavorably to Infosys and suggesting they misjudged demand. But the pricing is a collaborative exercise between the company (seeking maximum valuation) and the bankers (seeking maximum fees). The retail investor, sold on "anchor investor demand" and the "India Fintech Story," was the patsy in this equation.

The anchor investors—large institutions who get shares before the IPO—often have different time horizons, hedging strategies, or strategic reasons for investing. The retail investor has none of that protection. When the market corrects, retail is left exposed.

Synthesising the evidence—the 72% OFS structures, the ₹167 crore accounting gains, the ₹1,701 crore Net Loss hidden behind "Contribution Profit," the ₹324 crore banker fees, and the VC exits after lock-ins—we arrive at the uncomfortable truth:

The IPO process for Indian New-Age Tech Companies has become a systemic wealth transfer mechanism, not a capital formation event.

For the common investor—someone who knows nothing about boardroom deals, non-GAAP accounting, or merchant banker incentives—the realization comes too late. You bought into the "India Growth Story." You believed the headlines: "Lenskart Turns Profitable!" "Zomato IPO Subscribed 38x!" "Paytm: The Fintech Giant Goes Public!"

You invested your savings. Maybe ₹50,000. Maybe ₹2 lakh. You trusted the system—SEBI approved it, big banks underwrote it, anchor investors participated. How could it go wrong?

Then one morning, you check your portfolio. Paytm is down 75%. Zomato is down 60%. Your ₹2 lakh is now ₹50,000. And it's not your fault. You didn't have access to the boardroom. You didn't know about the OFS structure or the one-time gains. You couldn't decode the "Adjusted EBITDA" sleight-of-hand.

You were the exit liquidity. You were the mark. You've been had.

Traditionally, company insiders—promoters, founders, early investors—were expected to hold their stakes long-term. They were paid through dividends as the company grew. When the business matured and the time was right, they could exit gradually, at fair valuations.

But morals have gone to hell. The current model works like this:

The insiders aren't building long-term businesses—they're engineering exits. The IPO isn't about raising capital to grow; it's about cashing out before the market realizes the fundamentals don't justify the price.

This is the financial equivalent of road contractors: "Give me the money, and forget me." Except in the case of IPOs, it's done with legal documents, regulatory approvals, and the facade of legitimacy.

The market has already delivered its judgment:

These are not unfortunate market corrections. These are the predictable outcomes of a structurally flawed process.

The "India Growth Story" is real. India's digital economy, consumption boom, and demographic dividend are genuine macroeconomic trends. But buying them at any price is a fallacy.

Before investing in any IPO, ask these questions:

SEBI has begun to tighten disclosure norms—mandating better KPI reporting and forcing companies to justify their "Basis of Issue Price" more rigorously. But until these regulations are strictly enforced, the onus is on the investor to see through the golmaal.

The system isn't designed to protect you. The merchant bankers aren't your gatekeepers—they're salesmen for the selling shareholders. The "Adjusted EBITDA" isn't a sign of health—it's a distraction from the bleeding.

True capital formation builds businesses. The current model builds exits.

Until that changes, every retail investor must remember: When 70% of an IPO is OFS, when one-time gains inflate profits by 2x, when ESOPs are excluded from "Adjusted" metrics, and when bankers make ₹300+ crore in fees—someone is getting rich, and it's probably not you.

Golmaal hai bhai. Sab golmaal hai. The question is: Will you keep paying for the show, or will you demand a refund?

This exposé is based on forensic analysis of regulatory filings, financial disclosures, and expert commentary. All data and evidence cited from the following sources:

**All figures, quotes, and data points in this article are directly sourced from the above references and the original research document "The Great Indian Wealth Transfer: A Forensic Analysis of Structural Flaws, Valuation Engineering, and Retail Erosion in New-Age Tech IPOs." **

Sign up for the Daily newsletter to get your biggest stories, handpicked for you each day.

Trending Now! in last 24hrs

Trending Now! in last 24hrs