Adani’s Navi Mumbai Airport is a ₹20,000 Crore real estate pivot targeting 70% non-aviation revenue, functioning as a luxury "Aerotropolis" rather than just a transit hub.

Minaketan Mishra

Minaketan Mishra

If you drive down to the new Navi Mumbai International Airport (NMIA), you might think you are looking at a transit hub. You would be wrong.

For decades, the business of running an airport was simple but tough: you built a runway, airlines paid you landing fees, and you made a small margin. It was a "low margin, high liability" game. But the Adani Group doesn't play low-margin games.

The most revealing data point in their strategy isn't about planes—it's about the 70/30 Split.

Globally, the world's best airports (like Changi in Singapore or Dubai International) generate about 40-50% of their revenue from non-aeronautical sources (shopping, hotels, duty-free). The Adani Group has publicly set a target to derive 70% of their revenue from non-aeronautical sources by 2030.

This is a structural pivot. It means the aircraft are merely the funnel to bring high-net-worth individuals into a controlled ecosystem. The real product isn't the flight; it's the "City-Side Development"—a massive commercial engine where the airport becomes the destination itself.

Why this obsession with non-aeronautical revenue? Because of Regulatory Arbitrage.

In India, the Airports Economic Regulatory Authority (AERA) strictly caps how much profit an operator can make from "aeronautical services" (landing fees, parking, etc.). It’s a cost-plus model with limited upside.

However, there is no government cap on:

Adani has committed a staggering ₹20,000 Crore to what they call "City-Side Development" across their portfolio, with the lion's share going to Mumbai. The master plan for Navi Mumbai involves a 240-acre "Walkable Business District" featuring five luxury hotels (1,000 keys), three Grade-A office towers, and a massive retail precinct.

The strategy attacks Mumbai's biggest weakness: Friction. Currently, a global CEO landing in Mumbai faces a grueling 90-minute commute to Nariman Point or an unpredictable slog to BKC. In the Adani Aerotropolis, that friction is zero. You land, walk to your office, hold your board meeting, sleep in the hotel, and fly out.

This isn't just a convenience; it's an existential threat to the property valuations of South Mumbai.

If you have visited the new airport recently, you might have noticed a major problem: "Dead Zones." Your Jio or Airtel signal likely vanished the moment you entered the precinct.

This is not a technical glitch. It is a corporate battle for the "Nervous System" of this new private city.

To control the digital experience, Adani NMIAL has deployed a "Neutral Host" model. Instead of allowing telecom operators (Jio, Airtel, Vi) to install their own towers and antennas (known as "Right of Way" or RoW), Adani has built its own network and wants the telcos to rent it.

The Result? A standoff. The telcos have refused to pay, and the passengers are left with zero signal, forced to log in to the airport's public Wi-Fi. This turns the airport into a "Walled Garden" where the operator controls the digital pipe, effectively becoming a "Digital Gatekeeper."

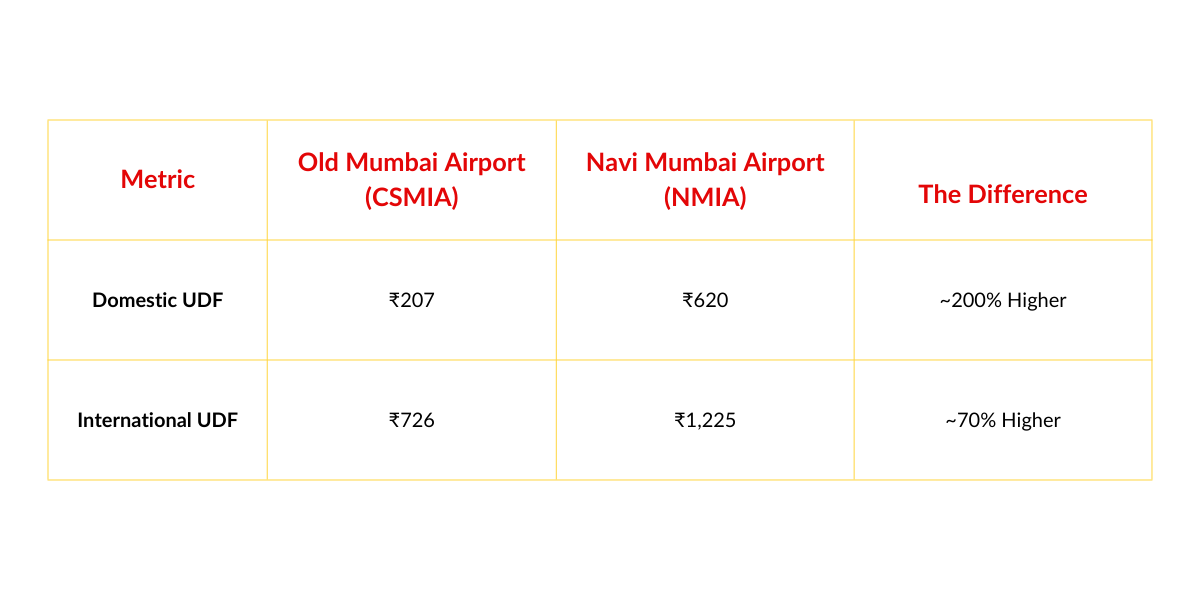

This luxury ecosystem comes with a price tag, and the consumer is footing the bill. The clearest indicator of this "Premiumization" strategy is the User Development Fee (UDF)—the tax you pay just to enter the airport.

The Insight: The ₹620 fee signals that NMIA is not trying to be a low-cost alternative for the masses. It is positioning itself as a premium product for the top 10% of income earners—the same people who will shop at the luxury malls and stay at the hotels.

The Navi Mumbai International Airport is a masterclass in modern business strategy. The Adani Group has effectively taken a public utility license and used it to build a private commercial fiefdom.

We often look at billionaires and ask "How?" The answer usually isn't luck; it’s structural engineering. Here is the playbook from the Navi Mumbai project:

In retail, a "loss leader" is cheap milk sold to get you into the store so you buy the expensive wine. Adani has applied this to infrastructure.

Why will a CEO pay a premium to stay at the Aerotropolis? Because the alternative is a 90-minute traffic jam.

Most developers let Jio or Airtel handle the connection. Adani said "No."

This is the most advanced move. Adani is using the definition of an "Airport" to build a "City."

Q: Why is there no mobile signal at Navi Mumbai Airport? A: It is due to a commercial dispute. Adani NMIAL wants telecom operators (Jio, Airtel) to use their "Neutral Host" infrastructure for a fee, while operators want to install their own equipment to avoid high costs.

Q: What is the Adani 70/30 Revenue Split? A: It is the Adani Group's strategic target to earn 70% of their revenue from non-aviation sources (retail, real estate) and only 30% from actual flight operations by 2030.

Q: Why are the charges (UDF) higher at Navi Mumbai Airport? A: The Domestic UDF is ₹620 compared to ₹207 at the old airport. This higher fee supports the massive "City-Side" infrastructure and positions the airport as a premium destination.

Disclaimer: This article is an analysis of public strategy documents and market data. It is for educational and informational purposes only.

Sign up for the Daily newsletter to get your biggest stories, handpicked for you each day.

Trending Now! in last 24hrs

Trending Now! in last 24hrs