India's new CAFE 3 norms mandate strict emission targets by 2027. While Maruti Suzuki argues the rules punish small cars, Tata Motors opposes concessions.

Brajesh Mishra

Brajesh Mishra

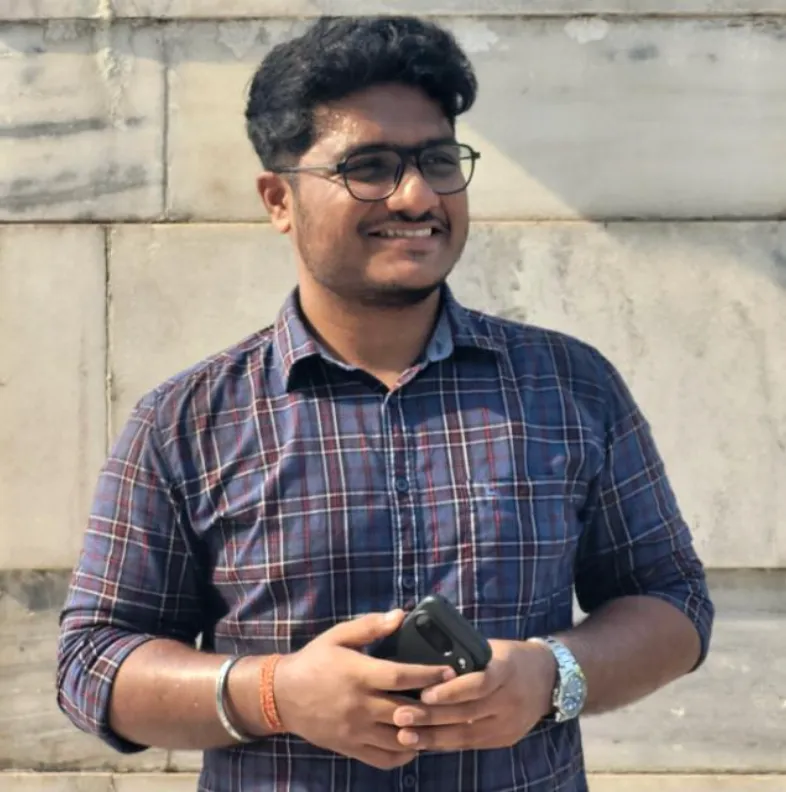

The Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE) has officially released the draft Corporate Average Fuel Efficiency (CAFE) Phase 3 norms, setting a stringent fleet-wide carbon emission target of 91.7 g/km for all carmakers in India, effective April 2027. This represents a significant tightening from the current ~113 g/km limit. The announcement has triggered an open conflict in the Indian auto industry, with market leader Maruti Suzuki arguing the new rules unfairly penalize small, fuel-efficient cars while inadvertently incentivizing heavier SUVs, creating a perverse "weight-based" loophole.

Since their introduction in 2017, CAFE norms have progressively tightened to push manufacturers toward greener technologies. Phase 3, however, introduces a critical shift: testing will move from the Modified Indian Driving Cycle (MIDC) to the globally standard Worldwide Harmonized Light Vehicles Test Procedure (WLTP), which is far more rigorous. This change makes the 91.7 g/km target even harder to achieve. The policy aims to force the adoption of EVs and hybrids, but its formula—which adjusts emission limits based on vehicle weight—has become the flashpoint of the current controversy.

While the headlines focus on "green goals," the deeper story is the "Brick in the Boot Paradox." The CAFE 3 formula (0.002 x (W – 1170) + c) mathematically rewards heaviness. It is paradoxically easier for a manufacturer to comply by making a car heavier (shifting it into a lenient target bracket) than by engineering a lighter, hyper-efficient vehicle that faces a punishingly low limit. This regulatory quirk incentives the very thing climate policy should oppose: massive, resource-heavy SUVs. We are witnessing a policy that might accidentally kill the eco-friendly small hatchback in the name of saving the environment.

For the consumer, this means the era of the cheap petrol car is ending. To meet the 91.7 g/km target, manufacturers will have to hybridize or electrify even their entry-level models, driving up costs significantly. The "small car concession" debate will likely determine the survival of the entry-level segment in India. If Tata prevails and concessions are denied, models like the Alto or Kwid may become commercially unviable. If Maruti prevails, the policy might be tweaked, but the broader trend toward expensive, tech-heavy vehicles is irreversible.

If a climate policy makes it easier to sell a 2-ton SUV than an 800kg hatchback, are we actually reducing emissions, or just gamifying the math?

What is the difference between CAFE 3 and CAFE 2 norms? CAFE 3 norms target a fleet-wide carbon emission average of 91.7 g/km, a sharp reduction from the ~113 g/km limit of CAFE 2. Additionally, CAFE 3 transitions testing from the MIDC cycle to the more rigorous WLTP cycle.

Why are Tata and Maruti fighting over CAFE 3? Maruti argues the weight-based formula unfairly penalizes lightweight small cars while favoring heavier SUVs. Tata opposes any special relaxation for small cars, arguing that reducing weight to meet targets could compromise vehicle safety.

Will car prices increase after CAFE 3 implementation? Yes. To meet the strict 91.7 g/km target, manufacturers will likely have to incorporate expensive technologies like strong hybrids, EVs, or advanced turbo-petrol engines, driving up the cost of vehicles, especially in the budget segment.

How do CAFE norms calculate CO2 targets based on weight? The norms use a regression line formula based on vehicle curb weight: Target CO2 = a x (W – b) + c. This means heavier vehicles are permitted a higher CO2 emission limit than lighter vehicles, creating an incentive for manufacturers to build heavier cars.

News Coverage

Research & Analysis

Sign up for the Daily newsletter to get your biggest stories, handpicked for you each day.

Trending Now! in last 24hrs

Trending Now! in last 24hrs