Typhoon Kalmaegi has killed nearly 200 across the Philippines and Vietnam and displaced over 560,000. Forecasts were accurate — infrastructure and governance failed.

Sseema Giill

Sseema Giill

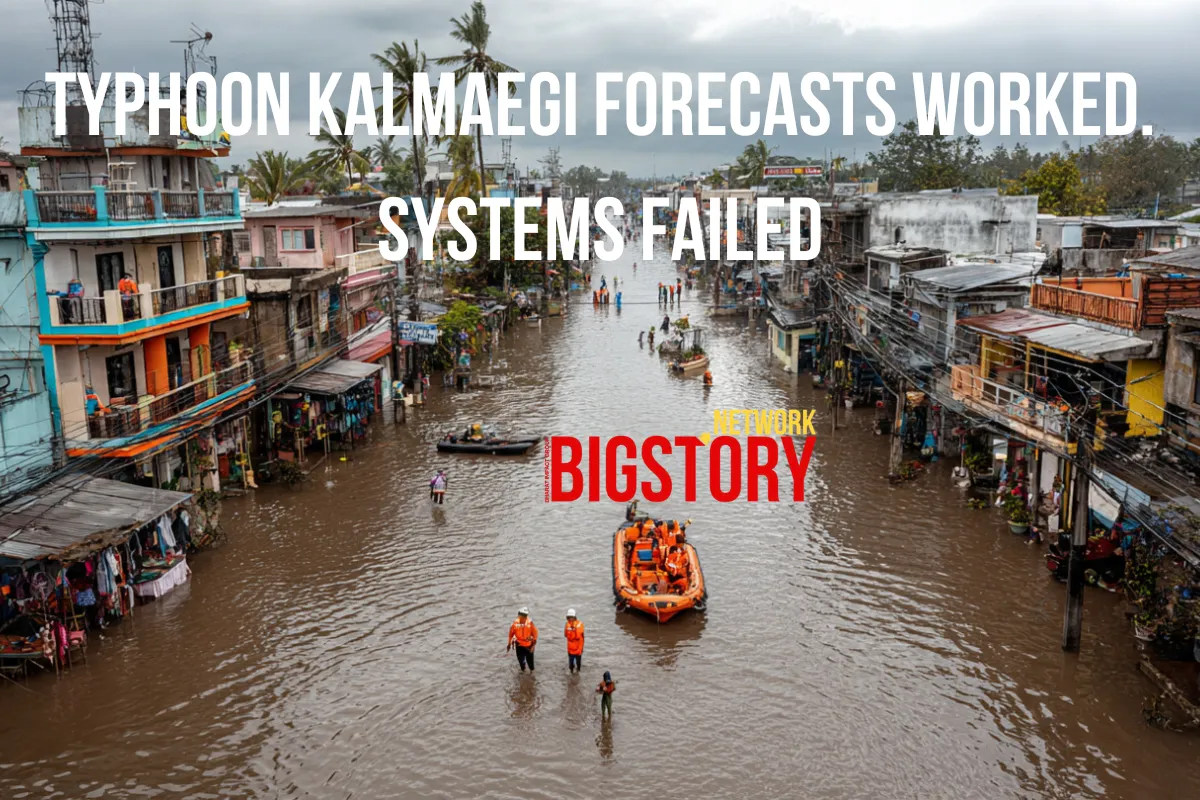

Typhoon Kalmaegi ripped through the central Philippines and later central Vietnam this week, killing at least 188 people in the Philippines and 5 in Vietnam, leaving 135 missing and displacing more than 560,000 across the region. Cebu province — hit by unprecedented 24-hour rainfall — suffered the worst losses and has become the focal point of national outrage after officials and residents linked the scale of destruction to years of quarrying, weak flood-control projects and alleged corruption. The disaster landed as world leaders opened COP30 in Brazil, turning a weather catastrophe into a live demonstration of the gap between climate science, early warning and real-world protection.

Kalmaegi formed in late October and underwent rapid intensification as it entered the Philippine Area of Responsibility. By November 4-5 it made landfall in the central Philippines, dumping what amounted to more than a month’s normal rainfall in 24 hours across parts of Cebu and surrounding islands. Infrastructure failures — bridges, roads and flood-control works — collapsed under the torrent. The Philippines declared a state of national calamity to unlock emergency funds and speed procurement; hundreds of thousands sought shelter. Before relief could fully mobilize, Kalmaegi regained strength over the South China Sea and struck central Vietnam, cutting power to over a million households and further stressing regional rescue capacities. A second storm, Fung-Wong, was then forecast to strike the north Philippines within days — compounding the crisis and limiting recovery windows.

President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr.’s state-of-calamity declaration mobilized national resources but also opened political questions about preparedness and infrastructure oversight. Cebu’s governor flagged quarrying and “substandard flood control infrastructure” as central causes of the catastrophic flooding, a charge that has sparked public outrage and calls for probe into procurement and construction standards.

On the science front, climate researchers stressed that record-warm ocean surface temperatures in the western North Pacific and the South China Sea amplified Kalmaegi’s intensity and rainfall. Rapid-intensification forecasts from advanced AI-enhanced models gave forecasters early, accurate warnings — but the loss of life shows that forecasting does not automatically equal protection.

Kalmaegi exposes a stark, growing mismatch: prediction has outpaced protection. Modern AI-assisted models flagged Kalmaegi’s intensification with unprecedented accuracy, and satellites warned of extreme rainfall days in advance. Yet those forecasts collided with fragile governance, decades of compromised infrastructure, and the logistical limits of disaster response. The result is a brutal, predictable paradox: science hands governments a warning on a silver platter, but institutional rot and underinvestment turn that warning into mobilized grief.

Put another way — Kalmaegi is not primarily a meteorological failure. It’s a governance failure amplified by climate change. Officials could see the storm coming; they could not, in many places, prevent it from becoming a calamity.

Cebu’s catastrophic flooding is now politically explosive because it appears preventable. Local leaders point to years of unchecked quarrying that filled rivers with silt, and to flood-control works that either failed or were built to substandard specifications. If investigations confirm systemic procurement fraud or deliberate corner-cutting, Kalmaegi will be read not only as a climate tragedy but as a case study in how corruption converts natural hazards into mass fatalities.

Kalmaegi landed as delegates gathered at COP30, and scientists are already quantifying human fingerprints on the storm’s behavior. Attribution studies using historical data and AI modeling indicate that extreme precipitation and the odds of multiple high-impact storms in a short period are now measurably higher because of human-caused warming. This disaster sharpens the conversation at COP30: mitigation remains vital, but adaptation funding and governance reform are now urgent survival tools for frontline nations.

Beyond immediate deaths and displacement, Kalmaegi threatens economic stability. Vietnam’s central highlands — an important robusta coffee region — saw heavy rains during harvest; even localized crop losses can ripple into global commodity volatility. Repairing destroyed roads, bridges and power lines will strain national budgets and delay recovery, especially when a second typhoon is still inbound.

We can now see extreme storms coming with machine-level clarity. The urgent question Kalmaegi leaves behind is blunt: will the world fund and enforce the governance fixes that actually turn those forecasts into saved lives — or will prediction simply become a better way to measure preventable death?

Q: How many people died in Typhoon Kalmaegi?

A: At least 188 confirmed dead in the Philippines and 5 in Vietnam, with dozens still missing (numbers evolving).

Q: Why was the flooding in Cebu so severe?

A: Exceptional rainfall in 24 hours—combined with quarrying, river siltation and alleged substandard flood-control works—amplified the flooding.

Q: Could the disaster have been predicted?

A: Yes. Modern forecasting — including AI-enhanced models — accurately predicted Kalmaegi’s rapid intensification and heavy rainfall.

Q: If prediction worked, why did people die?

A: Prediction alone doesn’t protect people. Failures in infrastructure design, procurement, evacuation capacity and emergency logistics converted a forecast into a catastrophe.

Q: What next — is another storm coming?

A: At the time of reporting a second system (Fung-Wong) was forecast to threaten the northern Philippines within days, complicating recovery.

Sign up for the Daily newsletter to get your biggest stories, handpicked for you each day.

Trending Now! in last 24hrs

Trending Now! in last 24hrs