JD Vance’s comment hoping his Hindu wife embraces Christianity sparks debate on faith, identity, and the line between personal belief and public power.

Sseema Giill

Sseema Giill

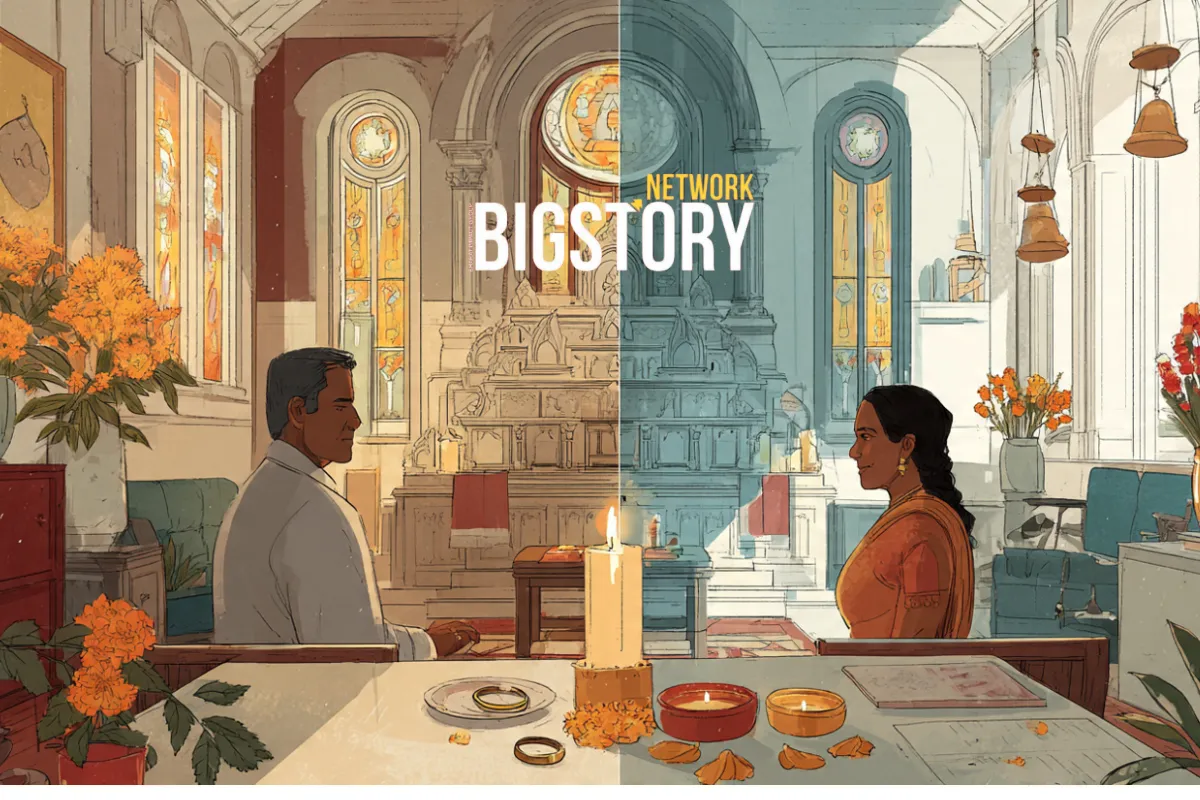

A Vice President hopes his wife will one day embrace his faith. Critics say he erased hers. The truth sits in a more uncomfortable space: what happens when private belief collides with public power.

At a crowded Turning Point USA campus event in Mississippi this week, U.S. Vice President JD Vance was asked a personal question by a young Indian-American attendee: how does his inter-religious marriage work, and what role does faith play in it?

Vance answered plainly. Yes, he hopes his wife Usha — a practicing Hindu — will one day come to Christianity. Yes, he believes in the gospel deeply enough to want her to share it. And yes, he sees that desire as an expression of love, not disrespect.

Hours later, the internet erupted.

Progressives accused Vance of publicly undermining his wife’s identity. Indian commentators accused him of religious paternalism. Hindu groups in the U.S. described the remark as casually disrespectful to their faith tradition. Interfaith advocates flagged it as a case study in “spousal conversion pressure.”

Vance’s response was defiant. Critics were displaying “anti-Christian bigotry,” he wrote, arguing that sharing one’s faith is intrinsic to Christian belief and that his wife’s autonomy remains intact.

A single sentence about a deeply personal subject became a referendum on power, cultural boundaries, and the politics of religion in America.

This wasn’t just an internet firestorm. It was a collision of three forces shaping modern politics: identity, faith, and performative authenticity.

On its face, Vance’s statement reflects something common in interfaith marriages: one partner hopes the other will someday join their spiritual path. Millions of couples navigate this without controversy.

The backlash wasn’t only about what he said — it was about where and why he said it.

He was speaking not in a private interview with nuance, but on stage before thousands of young conservative activists, many of whom come from circles where Hindu beliefs have been caricatured and denigrated. Online, Usha has previously been targeted by extremist elements with slurs for her faith. In that context, critics argue, Vance’s comment felt less like private vulnerability and more like public alignment with a dominant faith base.

Supporters counter that the Vice President shouldn’t have to self-censor his beliefs to avoid bad-faith interpretations — and that expecting Christians to hide their convictions is a form of bias.

What’s clear is this: the reaction wasn’t really about theology. It was about belonging and social power.

Usha Vance has previously spoken openly about her Hindu upbringing, her family’s traditions, and her lack of intention to convert. In past interviews, she was even credited with encouraging JD to rediscover his faith — making her Hindu identity not an obstacle in his spiritual life, but a catalyst.

She has not spoken in response to this controversy.

That silence — whether personal choice or political necessity — is part of the story. When one partner holds high office, the other often loses the freedom to narrate their own identity. Her name trends; her voice does not.

This moment exposes that burden. The politics of visibility can swallow the privacy of belief.

Vance’s remark unfolded in a moment where religious identity is increasingly tied to political signaling. In parts of the U.S. conservative movement, being openly Christian is framed as an assertion of cultural strength; in elite political circles, interfaith marriages often symbolize pluralism. Vance is straddling those worlds.

His comment pressed two cultural alarm buttons at once:

This is the tricky part: both groups aren't wrong to feel what they feel.

For pluralistic societies, that’s the uncomfortable middle ground — freedom of belief includes the freedom to hope, and the freedom to resist that hope.

The real question is not whether Vance loves his wife or respects her autonomy. It’s whether leaders can separate personal conviction from public representation of millions who do not share it.

Not “should spouses hope each other convert?”

The more revealing question is:

When leaders share private beliefs publicly, does it express authenticity — or impose identity?

The answer depends less on the belief and more on power, audience, and context.

Religion in politics is not new. But in an era where personal narrative fuels political legitimacy, intimate lives become rhetoric. That carries a cost — often paid by the quieter partner in the marriage.

Did JD Vance say his wife should convert?

He said he hopes she one day embraces Christianity — not that she should, or will.

Is his wife Hindu?

Yes. She has publicly identified as Hindu and has said she does not intend to convert.

Why did people object?

Critics argue he referenced his wife's faith in a setting where it served as political signaling, framing her belief as incomplete or inferior.

Did Vance apologize?

No. He said criticism amounted to anti-Christian prejudice.

Is this about interfaith marriage?

Partly — but more fundamentally, it's about how private belief is used in public life.

Sign up for the Daily newsletter to get your biggest stories, handpicked for you each day.

Trending Now! in last 24hrs

Trending Now! in last 24hrs