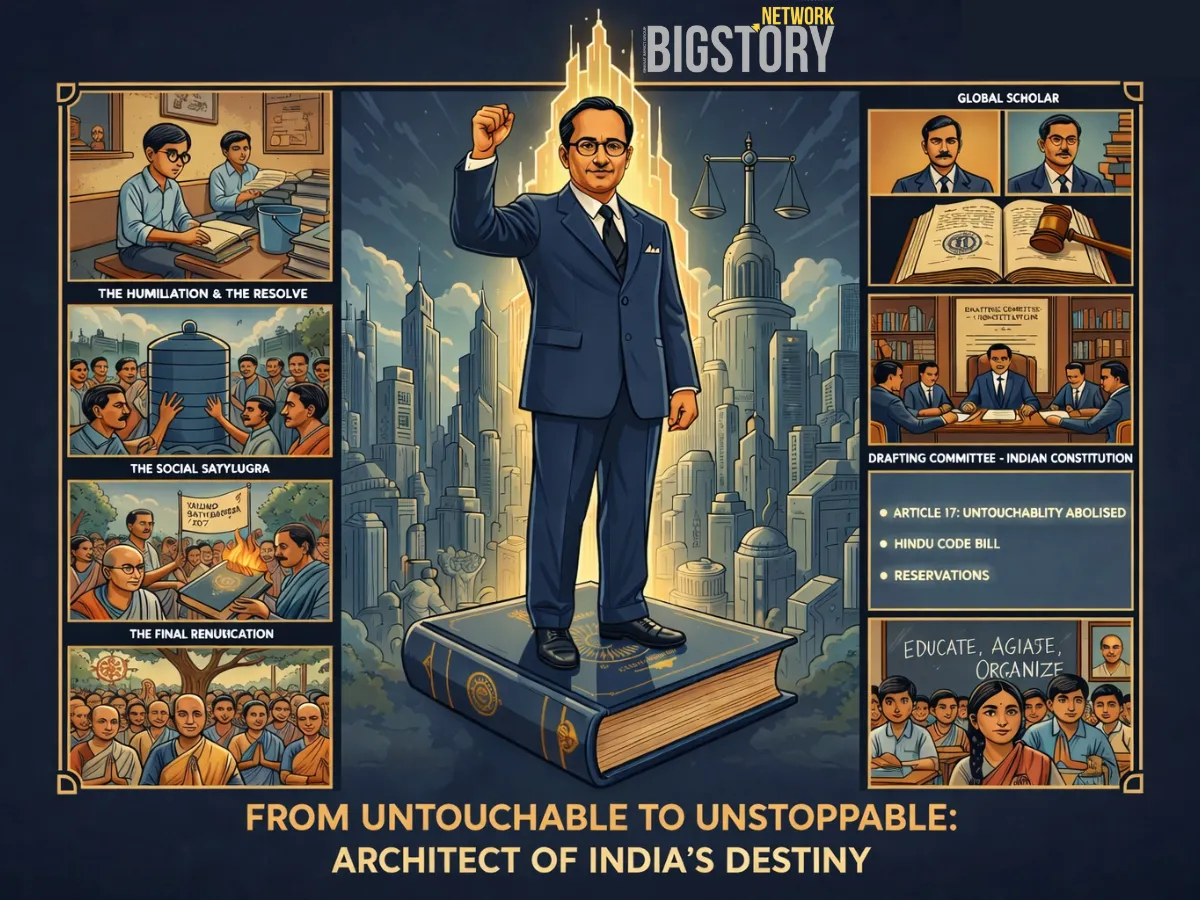

Explore the powerful journey of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar—from a child denied water to the Father of the Indian Constitution. A definitive story of his fight against caste, the Mahad Satyagraha, and his radical vision for equality.

Rashmeet Kaur Chawla

Rashmeet Kaur Chawla

Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar stands as one of the most influential figures in modern Indian history. As the principal architect of the Indian Constitution, a relentless social reformer, economist, and scholar, Ambedkar's contributions fundamentally shaped India's democratic framework and continue to inspire millions in their pursuit of equality and justice. His life's work centered on dismantling caste discrimination and establishing a society based on liberty, equality, and fraternity.

Despite facing tremendous social barriers, Ambedkar displayed exceptional academic brilliance. With support from the progressive Maharaja of Baroda, Sayajirao Gaekwad III, he became one of the first Dalits to receive higher education. In 1913, he earned a scholarship to study at Columbia University in New York, where he obtained a Master's degree in Economics and later a Ph.D. in 1927. His doctoral thesis, "The Problem of the Rupee: Its Origin and Its Solution," showed his deep economic understanding.

This exceptional educational background made him one of the most qualified Indians of his generation, equipped with both Western democratic ideals and a profound understanding of India's social realities.

“Was the architect of India’s Constitution also its sharpest critic? And could the man who enshrined equality in law foresee that caste would survive—even thrive—long after the Constitution came into force?”

This is the enigma that makes Dr. B.R. Ambedkar one of the most intellectually complex figures in modern history—a victim who became a visionary, a constitutional architect who warned that his own creation might need to be burned.

"No Peon, No Water": When Dignity Became a Demand

Born in 1891 in Mhow into the Mahar community, Babasaheb Ambedkar's early life was marked by systematic degradation. As a young "untouchable" student, Baba Ambedkar had to sit on a gunny sack outside the classroom, segregated from his upper-caste peers. He could only drink water when a peon was available to pour it from a height ensuring no physical contact that might "pollute" the water source. Later, he would sum up that childhood humiliation in bitter words: "No peon, no water."

This wasn't merely discrimination; it was a calculated technology of exclusion that taught Dalit children their designated place in the social hierarchy. The classroom segregation at Satara school became a crucible moment—transforming personal pain into a lifelong mission to dismantle barriers through knowledge and law.

From this foundation of humiliation emerged one of the most educated Indians of his generation. The child denied a glass of water would go on to earn doctorate degrees from Columbia University and the London School of Economics, and be called to the Bar at Gray's Inn in London. This wasn't ambition for its own sake—Ambedkar pursued economics, sociology, and law as weapons to expose and dismantle the caste system's structural flaws.

His educational journey through Elphinstone College, Columbia University (MA, PhD), London School of Economics (MSc, DSc), and Gray's Inn armed him with the analytical tools to critique caste not just morally, but economically and legally.

He believed knowledge dismantles the denial of dignity—education was resistance, not merely advancement.

Professional life would reinforce these lessons. After his Baroda scholarship, high-caste colleagues shunned him, refusing to work alongside a Dalit scholar. These repeated humiliations crystallized his worldview: the world operates like a rigged hierarchy that crushes dignity through inherited inequality, and justice can only be achieved through the annihilation of caste via law, education, and fraternity.

Ambedkar's return to India marked the beginning of his systematic campaign against untouchability and caste discrimination. Unlike reformers who sought gradual change, Ambedkar believed that the caste system was inherently oppressive and required radical transformation. He launched several social movements to establish the rights of Dalits, including the right to access public water sources, enter temples, and receive education.

Ambedkar was not merely a victim of caste—he analyzed it with scholarly precision. In his groundbreaking paper "Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis and Development," he revealed caste as a social mechanism created when endogamy (marriage within the same caste) was imposed on an exogamous population (one that marries outside the group).

This was revolutionary: Ambedkar demonstrated that caste was a man-made social technology of exclusion, not a natural or divine destiny.00000

In his most incendiary work, "Annihilation of Caste" (1936), Ambedkar went further. He argued that caste had "no scientific basis" and that India would remain fundamentally disunited without its complete abolition. Superficial measures like inter-dining and inter-marriage were insufficient. True change required destroying "the religious notions upon which caste is founded"—a radical critique that targeted Hindu scriptures directly, particularly the Manusmriti.

This wasn't just theory. On December 25, 1927, Ambedkar led followers in publicly burning the Manusmriti—the ancient text that codified caste hierarchies. This date is now commemorated as Manusmriti Dahan Din by many within the Dalit movement, symbolizing the rejection of scriptural justification for inequality.

Ambedkar's revolutionary vision manifested in organized action. In 1927, he led the Mahad Satyagraha, marching thousands of Dalits to drink from the Chawdar Tank—a public water source barred to "untouchables." This wasn't a chaotic protest but a structured confrontation using legal arguments about public rights. He believed systemic rituals perpetuate subjugation and demanded logical, organized challenge to overthrow them.

Ambedkar's most intense political struggle was not with orthodox Hindus but with Mahatma Gandhi over political safeguards for Dalits. The Communal Award of 1932 had granted the Depressed Classes (Dalits) separate electorates—allowing them to elect their own representatives independently. Ambedkar supported this as essential for a genuine political voice.

Gandhi opposed it, fearing it would divide the Hindu community, and began a fast unto death from jail. Under enormous moral pressure, Ambedkar signed the Poona Pact, replacing separate electorates with reserved seats within a joint electorate. While the number of reserved seats increased, Dalits' political voice remained locked within the Hindu fold. This was a compromise that many later lamented: protective measures for political representation, but no truly distinct voice.

It revealed the central tension in Ambedkar's life—the conflict between power and dignity, between working within systems to change them and maintaining the autonomy to challenge them completely.

As chairman of the drafting committee, Ambedkar used the Constitution to continue the battle through institutional design:

Article 14 established equality before law Article 15 banned discrimination based on religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth Article 17 abolished untouchability and made its practice punishable. Reservations created affirmative action in public employment and education for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. Ambedkar believed mere laws fail without tools enforcing dignity. The Constitution embedded liberty, equality, and fraternity as structural principles, prioritizing real empowerment over symbolic gestures.

The Constitution's Greatest Critic

Yet Ambedkar remained the Constitution's fiercest critic. In Parliament in 1953, he shocked followers by declaring: "I was a hack in constitution-making. I shall be the first person to burn it out. I do not want it. It does not suit anybody."

He warned that formal legal equality meant nothing while social and economic inequalities persisted. The Constitution was a tool, not a solution. If it failed to deliver justice, it deserved destruction.

As India's first Law Minister in Nehru's cabinet, Ambedkar drafted the Hindu Code Bill, which sought to modernize Hindu personal law, granting women rights in inheritance, marriage, and adoption. The bill faced severe opposition from conservative elements, and when the government hesitated to pass it in its original form, Ambedkar resigned from the cabinet in 1951, demonstrating his unwillingness to compromise on matters of social justice.

Ambedkar's vision extended far beyond caste. As Law Minister, he championed the Hindu Code Bill to grant Hindu women rights to divorce, property inheritance, and adoption. This challenged patriarchal structures with the same zeal he applied to caste hierarchies. For him, all forms of inherited inequality—whether based on caste or gender—required systematic dismantling.

Where Indian nationalism glorified village life as authentic and pure, Ambedkar described the Indian village as "a sink of localism, a den of ignorance, narrow-mindedness and communalism." This was provocative but logical: villages were where caste oppression was most entrenched, where social surveillance enforced hierarchy most ruthlessly. Glorifying village life meant indirectly glorifying caste oppression.

An economist by training, Ambedkar recognized that caste was fundamentally an economic system. It created barriers to labor mobility and capital movement, making economic development impossible without social reform. He developed a vision of state socialism within a democratic framework—advocating for state ownership of agricultural land, public control of essential resources, and planned distribution.

This wasn't communism, which he saw as authoritarian. Instead, Ambedkar proposed democratic control of economic resources to prevent the accumulation of wealth along caste lines, recognizing that economic power would always recreate social hierarchies if left unchecked.

By the mid-1930s, Ambedkar had publicly declared Hinduism an "oppressive religion" incompatible with human dignity. In his last years, he would say: "I was a Hindu at first but I won't be a Hindu even at my death"—signaling his complete defection from the system that had degraded him.

On October 14, 1956, in Nagpur, Ambedkar converted to Buddhism alongside his wife, followed immediately by a mass ceremony of nearly 500,000 followers. They took 22 vows that directly repudiated caste hierarchies and Hindu gods.

In his final book, The Buddha and His Dhamma, Ambedkar presented Buddhism as an alternative to both religious oppression and Marxist materialism. Genuine revolution, he argued, must simultaneously transform material conditions and the human mind. You cannot dismantle external hierarchies while leaving mental conditioning intact, nor can you change consciousness without addressing economic realities.

Ambedkar was a prolific writer and scholar. His works include "Annihilation of Caste," "Who Were the Shudras?" "The Untouchables: Who Were They and Why They Became Untouchables?" and "Buddha or Karl Marx." These writings combined historical analysis, sociological insight, and passionate advocacy, challenging orthodox interpretations of Indian history and society.

"Annihilation of Caste," originally written as a speech that was never delivered because organizers cancelled the event fearing controversy, remains one of the most powerful critiques of the caste system ever written. In it, Ambedkar argued that caste cannot be reformed and must be destroyed at its ideological roots. The text continues to influence social justice movements globally.

Dr. Ambedkar has been commemorated through countless statues, airports, universities, and massive memorials. His Jayanti and Dhamma Chakra Pravartan Din draw enormous crowds. He was voted "the Greatest Indian" after independence in a nationwide poll, and leading economists like Amartya Sen have called him foundational to their thinking. Yet there's heated debate over how different groups invoke his legacy. Some political movements emphasize his role in creating the Constitution and his nationalism while downplaying his scathing critique of the Manusmriti, his attacks on Hindu theology, and his warnings against hero-worship in politics. This selective appropriation—whether by the RSS, BJP, or others—raises questions about whether they honour Ambedkar or merely his image.

Dr. Ambedkar's life offers a clear lesson: reject pity for the oppressed, for sympathy chains them to victimhood. Instead, demand that every individual wield education as ammunition to shatter silence and privilege. His challenge echoes across generations: inherited power is no shield. Systems that hoard dignity must be rewritten or allowed to perish in their own contradictions. The path forward requires rising as architects, not beggars—annihilating oppressive structures through law, logic, and unyielding fraternity.

He advised them to "educate, agitate, organize"—and keep questioning whether the systems under which they live are just, or merely inherited.

His resolution to the conflict between power and dignity came not through defeating the system but through redesigning it. He evolved from excluded victim to constitutional architect, from protester to lawmaker and system builder. His belief in engineered justice transformed him from someone locked out of classrooms to someone who rewrote the rules governing the entire nation.

The paradox remains: Can a system built by the oppressed truly liberate them? Or does every Constitution contain the seeds of its own obsolescence, requiring each generation to burn and rebuild according to evolving demands for justice?

Ambedkar would say: if the system fails to deliver dignity, be the first to set it ablaze.

BIGSTORY BELIEVES: Every Person Is Made Equal by Existence, Not by Permission

This is a BIGSTORY because it is not merely the biography of a man it is the blueprint of a civilizational reset. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s life proves that education is the most radical form of power ever created: it turns humiliation into clarity, exclusion into authorship, and silence into law. From a child denied water to a mind that defined equality.

Dr. Ambedkar demonstrated that no human being is born inferior; every person is made equal by existence itself, not by caste, scripture, or social approval. A society survives not by preserving tradition, but by questioning it—and the most powerful revolution begins in the classroom, where minds are freed before laws are written.

Who is the father of the Indian Constitution?

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar is known as the "Father of the Indian Constitution." As the Chairman of the Drafting Committee, he played the principal role in framing the document that established India as a democratic republic and enshrined fundamental rights for all citizens.

What was the Mahad Satyagraha?

The Mahad Satyagraha of 1927 was a non-violent resistance movement led by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar. It asserted the rights of Dalits to use water from a public tank in Mahad, Maharashtra, challenging the practice of untouchability and asserting equal access to public resources.

Why did Dr. Ambedkar burn the Manusmriti?

Dr. Ambedkar burned the Manusmriti on December 25, 1927, as a symbolic protest. He viewed the ancient text as the codification of caste laws that justified social inequality and the oppression of Dalits and women. The day is commemorated as Manusmriti Dahan Din.

What is the significance of the Poona Pact?

The Poona Pact (1932) was an agreement between Dr. Ambedkar and Mahatma Gandhi. It resulted in reserved seats for the "Depressed Classes" within the general electorate, replacing the separate electorates that had been granted by the British Communal Award, which Gandhi opposed.

Why did Dr. Ambedkar convert to Buddhism?

Dr. Ambedkar converted to Buddhism in 1956 because he believed Hinduism perpetuated caste discrimination and was incompatible with human dignity. He saw Buddhism as a rational, egalitarian religion that offered a spiritual path free from social hierarchy.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/B._R._Ambedkar

https://ruralindiaonline.org/en/library/resource/dr-babasaheb-ambedkar-writings-and-speeches-vol-1/

https://triumphias.com/blog/ambedkar-and-dalit-movements/

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Bhimrao-Ramji-Ambedkar

https://www.sci.gov.in/centenary-of-dr-b-r-ambedkars-enrolment-as-an-advocate/

https://judicialacademy.nic.in/sites/default/files/1458100632_Ambedkar1.pdf

Sign up for the Daily newsletter to get your biggest stories, handpicked for you each day.

Trending Now! in last 24hrs

Trending Now! in last 24hrs