At Valdai 2025, Putin announced Russia will import more Indian farm and pharma products to balance oil-heavy trade and counter U.S. tariffs.

Sseema Giill

Sseema Giill

On the shores of Sochi, at the Valdai Discussion Club on October 2, 2025, Russian President Vladimir Putin took the stage with a message that carried both economic weight and geopolitical intent. Speaking to a packed forum, he admitted what many analysts had long pointed out: the booming oil trade with India had created a lopsided balance.

“More agricultural products may be purchased from India. Certain steps can be undertaken from our side for medicinal products, pharmaceuticals,” Putin said, hinting at a new chapter in Russia–India trade ties.

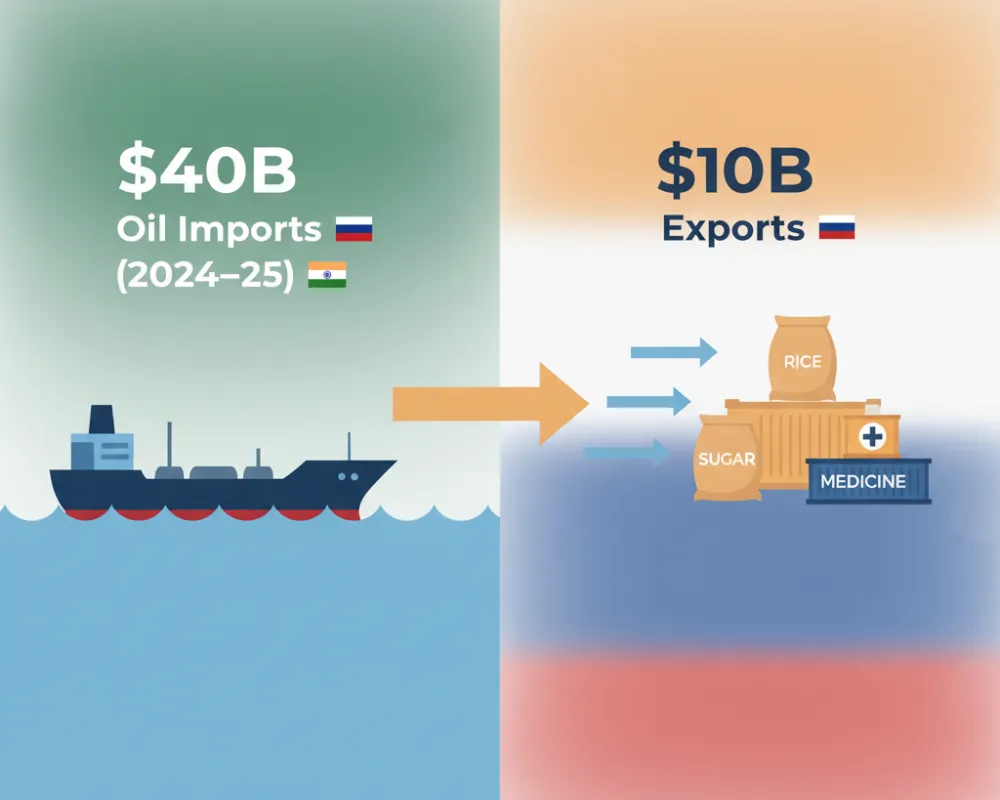

Over the past two years, India has become one of the largest buyers of discounted Russian crude, importing over $40 billion worth of oil in 2024–25 alone. But exports flowing the other way told a different story — less than $10 billion worth of Indian goods reached Russian shores.

This gap worried both governments. For New Delhi, the imbalance was worsened by the 50% punitive tariffs Washington slapped on Indian goods, cutting into already fragile export earnings. For Moscow, there was a diplomatic risk: it couldn’t afford to let a “strategic partner” feel shortchanged in trade.

From the Valdai stage, Putin offered a fix. He directed his government to increase imports of Indian agricultural products — everything from rice and sugar to edible oils — and to expand procurement of Indian pharmaceuticals, a sector where India holds global dominance.

The move was not just about economics. Putin framed it as a way for India to “balance losses from U.S. tariffs” while also asserting itself as a sovereign power, less vulnerable to Western trade policies.

Back in New Delhi, the announcement was greeted warmly. The Indian Commerce Ministry quickly highlighted new openings for farm and pharma exports, while the Federation of Indian Export Organisations called it a potential “game-changer” for Indian farmers.

Industry analysts, too, weighed in. Dmitry Rylko of IKAR pointed out that with Russia’s sunflower oil sector under strain, India could become a crucial supplier — a rare reversal, since India itself is one of the world’s biggest edible oil importers.

The story of this trade offset is not just about balancing books. It reflects how India and Russia are carefully reshaping their economic partnership in response to global pressure.

The timing is also strategic. Putin is set to visit India in December 2025, and the agricultural–pharmaceutical offset could headline a series of new agreements. Meanwhile, discussions within BRICS on setting up a grain exchange show that both countries are thinking long-term about breaking Western dominance in food and commodity trade.

For the plan to work, both sides will need to overcome logistical bottlenecks. Payment systems outside the Western banking framework must be strengthened. Shipping and storage networks for perishable goods need upgrading. And trust — often the hardest currency — must be maintained in a volatile global environment.

But if Moscow follows through, this could mark a new phase in the Russia–India “special and privileged strategic partnership”, one that moves beyond oil and arms into food security and healthcare.

As one Indian trade expert put it: “This isn’t just about rice and medicine. It’s about rewriting the rules of who trades with whom, and why.”

Sign up for the Daily newsletter to get your biggest stories, handpicked for you each day.

Trending Now! in last 24hrs

Trending Now! in last 24hrs